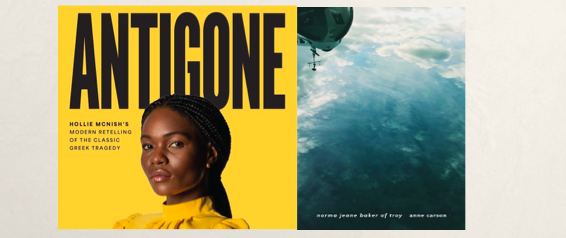

Although my research primarily focuses on novelistic adaptations of Greek myth, there are some opportunities to bring in poetry and plays. This blog post will focus on two dramatic contemporary rewritings of Greek myth. The first one is Hollie McNish’s adaptation of Sophocles’ Antigone. This adaptation was commissioned by Storyhouse as part of their Originals series, which invites writers to retell stories from across the ages to reflect on living in the present era. After that, the post will move onto Anne Carson’s Norma Jeane Baker of Troy (2019), which is a dramatic version of Euripides’ Helen that aligns Helen of Troy and Marilyn Monroe. This is something we have seen elsewhere, in Helen McLaughlin’s Helen and Carol Ann Duffy’s ‘Beautiful’.

For the myth of Antigone in its most famous iteration SEE HERE.

McNish’s Antigone premiered in autumn 2021, delayed from spring 2020 because of the coronavirus pandemic. It was co-produced with TripleC, a Manchester-based disabled-led organisation that supports access and representation for deaf, disabled and neurodivergent people across the arts and screen sectors. The inclusion of BSL and accessibility provisions for disabled and neurodivergent people was excellent, and there were also pre- and post-show workshops running alongside the programme! The casting of Fatima Niemogha as Antigone and Raffie Julien as Ismene was a stroke of genius.

First, it is worth noting that Anouilh’s 1944 adaptation is alluded to in Hollie McNish’s own adaptation of Sophocles’ Antigone. In the opening scene, Antigone says to Ismene:

And I know what you’re gonna say already, Izzy.

Oh Antigone! Calm down

Oh Antigone, life isn’t easy!

Oh there goes Antigone, daydreaming again! (McNish 2021: 11).

Here, Antigone specifically anticipates the words of Anouilh’s condescending Ismene. In Anouilh’s Antigone, Antigone becomes the almost petulant child (‘Little Antigone gets a notion in her head — the nasty brat, the wilful, wicked girl;’ [Anouilh, trans. Galantiére 1946: 11]) while Ismene is a frustrated older sister: ‘Listen to me Antigone. [...] I’m older than you are. I always think things over, and you don’t. You are impulsive. [...] Whereas, I think things out’ (11). Anouilh’s Ismene is explicit in both her assessment of her sister as a wilful youth and herself as a more measured, reasonable elder: ‘There you go, frowning, glowering, wanting your own stubborn way in everything. Listen to me. I’m right oftener than you are’ (11).

For Fleming, this 1944 play is a canonical aspect of Antigone’s reception, though there is a tension between those who see Antigone as an analogue for the French resistance and Creon as Nazi occupation, and those that interpret the play as collaborationist propaganda (Fleming 2008: 164-8). Fleming concludes that the play throws into stark relief the complication of casting Antigone as the poster-girl for feminism, yet ‘[f]ew now, if any, are concerned with Antigone’s lapse into fascism’ (186).

Anouilh’s play marks the beginning of the trend of rewriting Antigone as the younger sister, to emphasise her political prowess (whether in the service of far-right or more liberal ideologies).

|

| Jean Anouilh's ANTIGONE, The Wandering Theatre co. (source) |

McNish’s intertextual reference suggests an engagement with the history of adapting Antigone for later eras. Moreover, this signals that, in the same way that Anouilh was writing in the context of Nazi occupation, McNish is writing with the contemporary political climate in mind. McNish makes explicit the connection between Creon as an unjust and power-hungry ruler and former US president Donald Trump: ‘as I watched Donald Trump’s final speeches as US president [I thought] that’s just like Kreon’ (McNish 2021: xi). She presents this in the play by mirroring Trump’s speech patterns, exemplified by Creon’s repetition of ‘great’ when describing Eteocles as a ‘Brave soldier, loyal citizen, such a great, great man’ (31).

This is not the first time Creon’s demagoguery has been used to critique fascist politicians. In Three Guineas, Virginia Woolf said that Creon’s politics were ‘typical of certain politicians in the past, and of Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini in the present’ (Woolf 1938: 109). The Sophoclean drama ‘could undoubtedly be made, if necessary, into anti-Fascist propaganda’ and Woolf notes an ideological symmetry between Antigone and ‘Mrs Pankhurst, who broke a window and was imprisoned in Holloway’ (109).

For McNish, like Morales, Antigone’s characterisation hints toward Vanessa Nakate, Malala, and Greta Thunburg, since she is ‘very opinionated, believes deeply in her Gods [which, in Nish’s version, are the Earth and the Environment] but can be found annoying to listen to all the time by some people’ (McNish 2021: xxi). Antigone’s potential for left-wing political activism is exemplified in the play when she quotes the linguist and activist Noam Chomsky: ‘Obedience will always be the easiest option, Izzy / – that doesn’t make it right’ (21).

|

| Fatima Niemogha as Antigone in the Sophocles' tragedy at Storyhouse Chester (source) |

McNish has stated that part of the initial appeal of the play for her was that it passes the Bechdel test –– two named female characters speak to each other about something other than a man. This is not the only motif within Antigone that remains relevant; McNish lists the position of women in society, the unjust power of monarchy, the effect of power on men’s egos, the importance of speaking up against injustice and the difficulty in safely doing so (xii) as some of the aspects of the play that remain potent.

***

Anne Carson’s Norma Jeane Baker of Troy (2019) is a dramatic version of Euripides’ Helen that aligns Helen and Marilyn Monroe. Readers of the blog will know from the ‘Solving the Problem of Helen’ series (Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4) that Helen’s beauty has found analogues in women as far-ranging as Cleopatra, Marilyn Monroe, Jackie Kennedy, and Princess Diana. Like in Duffy’s poem ‘Beautiful’ and the 1995 National Theatre production of The Women of Troy, Carson’s poem uses the figure of Marilyn Monroe to draw a parallel between these two women who are deemed too beautiful to be happy.

|

| Norma Jeane Baker of Troy, Rough Magic theatre co. (source) |

As the title suggests, the two figures of beauty are conflated; indeed, the opening monologue, delivered by Norma Jeane Baker (the only cast member), claims that the Trojan War ‘was caused by Norma Jeane Baker, / harlot of Troy’ (Carson 2019: 7). Like Helen in Euripides’ play, Norma Jeane disputes this claim due to the eidolon: ‘That was all a hoax. / A bluff, a dodge, a swindle, a gimmick, a gem of a stratagem. / The truth is, / a cloud went to Troy.’ (7). The long list of synonyms for ‘hoax’ is juxtaposed against the short enjambment used to relay the ‘truth’. This imitates the polyphony surrounding Helen’s role in the war, as well as Euripides’ acquittal of her in the Helen. Once again, the comparison is made between Helen and Marilyn Monroe to demonstrate the construction, and then subsequent vilification, of beautiful women in the public psyche throughout history. This is clear in the lines:

Rape

is the story of Helen,

Persephone,

Norma Jeane,

Troy.

[...]

Oh my darlings,

they tell you you’re born with a precious pearl. Truth is,

it’s a disaster to be a girl. (17-8)

The repetition of ‘[t]ruth is’, as well as the devices of enjambment, lists, and omitted capital letters, reinforce that this an opportunity for maligned women deemed too beautiful to live to share their truths. The universality of this message is communicated via temporal and spatial displacements, such as setting the play in an amalgam of Troy and Los Angeles, while Arthur/Menelaus is king of Sparta and New York, and the Greek Army is conflated with MGM media. The analogues are not only drawn between Marilyn and Helen, since Persephone is also used as evidence; specifically, Persephone as she is portrayed in a poem by the Modernist Stevie Smith. The line ‘I was born good, grown bad’ (17) becomes a refrain throughout the play.

By engaging with the classical tradition in this manner, a sense of universality and authority is provided to Norma Jeane’s message.

This message is also reinforced in the HISTORY OF WAR LESSON interludes in the play, which offer pseudo-pedagogical and philological analyses of war. In the second lesson, ‘τραῦμα / “wound”’ (14), a pedagogical approach is taken. The statement ‘Euripides makes a hero out of Helen, who was brutalized by merely staring at war too long’ is followed by ‘TEACHABLE MOMENTS’ (Helen’s response to Menelaus’ violence against unarmed people) and ‘DISCUSSION TOPICS’ (to compare and contrast being speared and depressed) (14).

In the third lesson, ‘ἁρπάζειν / “to take”’, philology is used to encompass the message of the text: ‘if you possess a woman [...] or occupy a city, you are a taker’. ἁρπάζειν comes into Latin as rapio, from which the English language gets rape –– all are ‘words stained with the very early blood of girls, with the very late blood of cities’ (19). The conflict of the Trojan War, and all Western wars since, become indistinguishable from gender-based violence. The fifth lesson, ‘παλλακή / “concubine”’, explains the Ancient Greek definition of dirt as something out of place* and the linguistic relationship between the noun for ‘concubine’ and verb ‘to sprinkle’. This provides the ‘TEACHABLE MOMENT’ in the Iliad when Helen is weaving the events of the war, and Homer uses the verb ‘sprinkle’ to describe the embroidery (Ibid., 32). This implies that, on a linguistic level, there is a condemning connection between Helen being out of place (she is, therefore, dirt) as a Trojan concubine, and her sprinkling death into her tapestry. In light of this, the end of the play where Norma Jeane is knitting ‘every detail’ of the fall of Troy (including ‘every pointless prayer’ and ‘every bone that broke / in the baby they tossed over the wall on the last day’) (51-2) becomes an amplification of the dirty business of war, and a laundering of her own reputation as she focuses on telling her story and hoping to see her daughter again.

* Carson expands on this definition of dirt as something out of place in Men in the Off Hours (2000), a hybrid text of short poems and verse essays. In ‘Dirt and Desire: Essay on the Phenomenology of Female Pollution in Antiquity’, she repeats the metaphor of poached egg on one’s plate as not-dirty, while poached egg on the floor or a book page is dirty (Carson 2000: 148; Carson 2019: 32). For the Ancient Greeks, women were simultaneously polluted, pollutable, and polluting, due to their their wet (and therefore unhygienic) bodies and minds, their potential for defilement, and their insatiable sexual appetites (Carson 2000: 138-161).

***

These are two examples of where my research reaches beyond prose. Last summer, I went to see Kathy McKean’s Medea –– which was part of Glasgow’s Bard in the Botanics festival –– and it was truly spectacular. I’m hoping that I will get the opportunity to see more productions of Ancient Greek plays (and, of course, modern re-imaginings of them!) soon.

this was so brilliant I don’t even have the words. @Cooper1Nicole was an absolutely breathtaking Medea https://t.co/WhQPGLX1hh

— Dr. Shelby Judge 🌚 (@Judgeyxo) July 1, 2022

Comments

Post a Comment