Birthday blogpost! Birthday blogpost! Birthday blogpost!

My birthday is on the 15th March, which tells you that 1) I'm a Pisces, and 2) my birthday is on a Roman holiday, the Ides of March, so I share my birthday with Julius Caesar's death-day.

Caesar is the only person I am willing to share my birthday with: if you're reading this and thinking "oh cool my/someone I know's birthday is the same day" I am sorry to inform you that, no, it isn't. March 15th is my birthday – you have to change yours.

Anyway, my birthday was quite significant in antiquity, so I thought it would be fun to do a birthday blogpost on the mythos of march!

Constellation Myths

I'm a Pisces, which might mean that I'm compassionate and ambitious, depending on what you believe, but it definitely means that I was born between 19th February - 20th March, and that I'm going to tell you a myth about fish.

But first, some thoughts on constellation myths more generally.

As Robin Hard writes in the 'Introduction' to her translation of the Constellation Myths by Eratosthenes and Hyginus:

The night sky is an alien environment, filled with countless points of light set in no kind of order. It is rare for any group of stars to form any obvious pattern which might encourage people to think that they are looking at a plough or wagon, perhaps, or a cross or crown. In spite of this, a natural tendency has always existed for human beings to try to domesticate the sky by identifying groups of stars with earthly things, even if that task often requires some effort of the imagination. (Hard 2015: ix)

This is incredibly interesting to me. The idea that we as humans looked to the sky and were filled with a desperate, anxious need to organise it within a framework that we understand. Now, a question I find myself asking a lot: where do the myths come into this? Humans were looking at the sky and forcing it into a framework that we can properly conceptualise and, from there, it's understandable that we looked at these shining figures in the heavens and considered them in a religious framework. As Hard suggests, 'Perhaps the Maiden in the sky (Virgo) is the corn-goddess Demeter, because she is holding an ear of corn [...] or perhaps she is blind eyed Fortune because her head is faintly lit' (Ibid., x).

It wasn't just the Greeks who did this either - in the Renaissance, the constellation previously known as Heracles became the Kneeler, and Pegasus became simply the Horse. The Native Americans also have a complex understanding of constellations that are also named for, and associated with, their mythos and beliefs.

To return to the Ancient Greek astronomers, there is we call astral mythology: when myths were devised to explain how these things came to be set in the sky, as the result of events that had happened on Earth. In these instances, a deity must have intervened to transfer the being or item into the sky. The Lyre is the lyre that Hermes invented from the shell of a tortoise; the Crown is the gift given from Dionysus to his mortal bride, Ariadne. The astral myths here being that the gods commemorated their successes by preserving them in the sky.

|

| Van Gogh's Starry Night (1889) |

Hera's Crab attacked Heracles during his fight with the Lernaian hydra; Hera then elevated her Crab warrior to the sky to honour it (becoming The Crab of the Zodiac). The first clause of that sentence is a myth, the second clause is an astral myth.

Robin Hard calls this 'attaching a new end to an old myth' (Ibid., xii) which I particularly like because it illustrates a point that I make again and again in my research: retelling myths and altering them to fit your current purpose is an integral part of the mythic tradition - Homer, Sophocles, Euripides, and Ovid all did it, so why can't Margaret Atwood, Pat Barker and Madeline Miller? Or rather, why are their more recent contributions considered less integral to the mythic tradition than their ancient counterparts?

But there is another form of astral myths, ones where the whole myth is created to account for the shapes in the stars. This is the case with Orion and the Scorpion: Orion rises as the Scorpion sets, so it is as though the the Scorpion is chasing Orion. This led to the creation of the myth that Orion was pursued and killed by a giant scorpion sent by Artemis. Robin Hard calls these 'genuine star-myths' (Ibid., xiii), which I think is cute.

There are also Catasterisms to consider, which is a term that the Greeks invented to describe the process by which people or things are set in the sky. There's Callisto, who was transformed into a bear and, in turn, was then transformed into the constellation Great Bear. There's Castor and Pollux, the Dioscuri, brothers of Helen and Clytemnestra, who shared one immortality and alternated spending their time in Hades and on Olympus until Zeus elevated them to the sky, where they became Gemini.

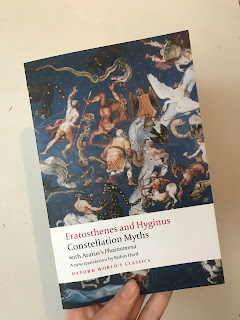

I promise I'll get on to talking about mythical fish soon, but first a quick note on the source I'm using, the Constellation Myths by Eratosthenes and Hyginus. Eratosthenes was an Alexandrian who aimed to 'compile an exhaustive compendium of astral myths, recounting tales to explain the origin of every constellation, often with variants and alternative myths' (Ibid., xvii). That work is now lost, but it did much of the work establishing the canon of constellation myths, and most constellation myths were ultimately derived from it. As well as telling all of the myths, Eratosthenes also listed the stars in each constellation in order to accurately locate each one, making it an incredibly useful resource for mythologists and astronomers alike.

Hyginus, meanwhile, was the later Latin author of Astronomy, which is a really interesting resource because it did not claim to be a comprehensive, scientific treatise, but rather a readable directory for the regular reader with an average education. Hyginus' Astronomy provides an introduction to the celestial sphere and the fundamentals of astronomy, but its largest section is on astral mythology. It is generally accepted nowadays that Hyginus drew almost all of his mythological material from one source: Eratosthenes. The Classical tradition is fraught with plagiarism, kids.

|

| 17th Century celestial by Dutch cartographer Frederik de Wit |

Constellation Myths: Pisces

Okay, I promised you a fish myth or two. As Hyginus explains (presumably via Eratosthenes), the Pisces constellation is comprised of two Fishes, the offspring of the Great Fish. One of the Fishes is called the Northern and the other is the Southern, and the fishes are linked by stars resembling a ribbon. The lower Fish has 17 stars, while the higher one has twelve. The point at which the fishes connect was called the 'celestial knot' by Cicero, indicating that the constellation is not just the two fishes but also the connecting ribbon (Hyginus Astronomy 3.29; trans Hard 2015: 83-4).

|

| Pisces constellation by KindredArtCollective |

Typhon was a monstrous giant serpent - in Greek myth, he is one of the deadliest creatures and he was known as the father of monsters, whom he begat with his mate Echidna, who was half-woman half-snake. Gaia (Mother Earth) sent Typhon to attack the Olympians, but they were warned by Pan and so they had time to flee. Pan turned into a goat-fish otherwise known as Capricorn, while Aphrodite and her son Cupid (who was a primary focus of last month's blog post) turned into two fishes and swam to safety.

According to Hyginus, this explains why Syrians do not eat fish - because they are worried that they will be eating gods or their offspring. Honestly, I have no idea why Hyginus believed that Syrians do not eat fish, or whether this was a belief that was so widely held that it needed an etiological explanation.

What I do know is that Syria seems to be central to the formation of the Pisces myth: Pan, in the form of Capricorn, jumps into the Euphrates river; in another version of the Pisces myth, an egg fell into the Euphrates river, then it was rolled to shore by fish, then it was nested by doves, until out of the egg hatched Aphrodite. As a sign of gratitude, Aphrodite put the fish into the night sky, as the constellation Pisces.

Robin Hard comments that fish were such an atypical part of Greek myth that they had to look to the East, as it were, for an explanation for the Fish in the sky. The mother goddess Derceto, known to the Greeks as the Syrian Goddess, had pools of sacred fish and was sometimes portrayed as being half-piscine* herself (Hard 2015: 85). For all of you mermaid enthusiasts out there, Derceto - otherwise known as Atargatis - was sometimes described as a mermaid goddess, and is sometimes cited in discussions about where we get the idea of mermaids from.

*half-fish: piscine means concerning fish - you can see where we get that from.

|

| Derceto, from Athanasius Kircher's Oedipus Aegyptiacus (1652) |

As an interesting aside: Purim is a Jewish holiday that falls at the moon preceding the Passover, which was set by the full moon in Aries, which follows Pisces. The story of the birth of Christ is supposedly the result of the spring equinox entering into the Pisces, as the Saviour of the World appeared as the Fisher of Men, thus mirroring entering into the Age of Pisces (Bobrick 2006: 10). I don't really have a point here, except that Pisces has been a religiously significant constellation throughout historical periods, across religious boundaries - we can see it in ancient Greek, ancient Syrian, and Abrahamic religions.

(Beware the) Ides of March

What is an Ide, anyway?

For the Romans, the Ides came every month because they did not count months in dates, but in three fixed points: the Nones, the Ides, and the Kalends. The Ides was the 15th day in 31-day months, the 13th day in hollow months. In March, the Ides were marked by religious observances and it was the deadline for settling debts.

Who was Julius Caesar?

You know, the Roman geezer.

Julius Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March in 44 BC. He was stabbed to death at a meeting of the Senate by up to 60 conspirators, led by Brutus and Cassius. According to Plutarch, a seer had warned Caesar that harm would come to him no later than the Ides of March; Caesar saw the seer again on his way to the Theatre of Pompey and joked that 'The Ides of March are come', suggesting that the seer was full of shit, to which the seer replied 'Aye, Caesar, but not yet gone' (Plutarch Caesar 63).

As sassy as that is, it is not the way we remember it. We remember William Shakespeare's version Julius Caesar, where Caesar is warned by a soothsayer to 'beware the Ides of March' (Act 3, Scene i). Classical Reception is important, people!

|

| The Death of Julius Caesar, Vincenzo Camuccini (1793) |

|

| Angus Jackson's production of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar for the RSC (2017) |

Caesar's death marks the end of the "crisis of the Roman Republic", that culminated in the end of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. Caesar's death triggered a civil war that resulted in the rise to sole power of his adopted heir Octavian, who was later known as Augustus. Ovid portrayed the murder of Caesar as sacrilegious since Caesar was a priest of Vesta, but that may well be because Ovid was writing under Augustus' rule. That didn't stop Ovid throwing shade and getting exiled by Augustus later, though.

On the fourth anniversary of Caesar's death in 40BC, Octavian executed 300 senators and equites who had fought against him, part of a series of actions attempting to avenge Caesar's death (see: Barden Dowling 2006; Keaveney 2007).

***

In writing this blog post, I realise that my birthday has a long and bloody history. An attack from the mythical monster of all monsters; Caesar stabbed by 60 conspirators; 300 senators murdered in retaliation. Let that be a warning to people, I suppose, not to upset me on my birthday.

|

| Throwback to my 21st birthday, with my darling mother |

Cover image: source

Comments

Post a Comment