This instalment of the Queering Mythology series is going to focus on a few myths of Big Gay Heroes in Greek myth.

Heracles

Let's start big, with Heracles. You know the guy with the 12 Labours, two wives and many other female sexual "conquests". As Harrity writes for Advocate (the LGBTQ+ news website), 'Hercules was a legendary stud with the ladies [... and] His love life with boys is no less active' (2013).

First up is Iolaus, who was Heracles' nephew and accompanied him on many of his Labours. It was said that Heracles performed his Labours with more pride when Iolaus watched. Heracles, who you out here stunting for? (Iolaus; he was showing off for his boyfriend). Most notably, when Heracles was battling the multi-headed Hydra, Iolaus helped by cauterising the necks as Heracles beheaded them.

In case you think that I'm just reading Bi representation where there is none, I'm happy to report that both Plutarch and Aristotle noted the romantic importance of Iolaus to this Olympian hero, and for centuries lovers would pay their respects to Iolaus' grave for good luck. The Thebans were such Heracles/Iolaus shippers that they worshipped them together, and named their gymnasium after him! I'm not saying that when Heracles died, Iolaus was honoured as his lover, but he did get the immense honour of lighting his funeral pyre... okay, I guess I am saying that.

Then you've got Hylas. When Jason sent out his call for heroes, and assembled the Argonauts, Heracles joined the party with his companion and servant Hylas. Hylas was either seduced or kidnapped by a group of nymphs who desired him. Brokenhearted, Heracles searched for him, and he took so long that the Argo set sail again without him. Again, I'm not saying that Heracles and Hylas' relationship has long been used to narrate male/male desire, but Oscar Wilde did write in The Picture of Dorian Gray of 'gilded a boy that he might serve at the feast as Ganymede or Hylas' (ch.11)... okay, once again, I guess I am saying that.

Thus, I offer you: Bisexual Heracles!!

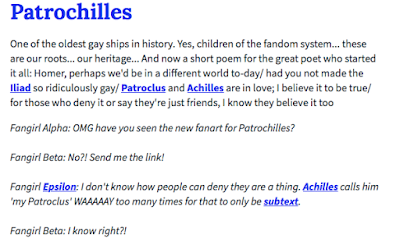

Patrochilles

|

| This is my ship okay, do not @ me |

In the Iliad, Achilles and Patroclus are close childhood friends that lead the Myrmidons to war in Troy; they hold each other in very high esteem, such as when Achilles calls him 'my prince, Patroclus' and 'Son of Menoetius, soldier after my own heart' (Homer, trans. Fagles). Their closeness is central to the plot of the Iliad, as it is the death of Patroclus by Hector's hand (spoilers, sorry) that incites Achilles to return to fighting, thus ensuring that Achilles will kill Hector in return. This ensures that Troy will fall, because it is prophesied that Troy cannot fall until Hector does; Achilles is really the only person skilled enough to kill Hector, but he knows that his death will shortly follow after Hector's. It's just tragedy all the way down.

As Edith Hamilton writes, Achilles declared that 'I will kill the destroyer of him I loved; then I will accept death when it comes' (1942: 271). You know, just friend things. Just like how Achilles is visited by the shade (or ghost) of Patroclus, who entreats him: 'Never bury my bones apart from yours Achilles, / let them lie together', which has long been understood as a declaration of their intimacy.

This relationship has been very famously adapted in recent years by Madeline Miller, in The Song of Achilles, winner of the Women's Prize for Fiction in 2012. This novel is one that I focus on heavily in my 'Queering Myth' chapter, analysing Achilles and Patroclus' relationship in the novel in terms of both ancient and modern notions of queerness.

There is one discussion in the chapter, in particular, that I think you will find interesting. In my last Queering Myth blog post, I discussed the erestes/eromenos socio-sexual relationship. In this one, I am going to talk about how Achilles and Patroclus map onto this dynamic. Firstly, it is important to note that their relationship was not pederastic (again, see last month's post for more information), and so they do not map very easily into the erestes/eromenos framework. In Classical discourse, Achilles and Patroclus are cited as an example of an un-ideal pederastic couple, as they 'were similar in age, and there is much dissension as to which of them was the erastes and which was the eromenos' (Holmen 2010). This debate comes to us directly from ancient source texts, as Aeschylus' tragedy Myrmidons has Achilles as the lover, and Patroclus as the loved, while in Plato's Symposium, Phaedrus calls Aeschylus' interpretation 'nonsense' (Plato, 178A-185C: 183 in Holmen 2010). Instead, Plato opines that 'Quite apart from the fact that he was more beautiful than Patroclus... and had not yet grown a beard, he was also, according to Homer, much younger'.

So, even in Antiquity, thinkers were debating who was the top and who was the bottom in Patrochilles. Who, then, am I to shy away from asking the same questions? Though please don't go away thinking that I am the only modern-day person wondering about this, because if the large fan-following for Achilles/Patroclus and TSOA on 'Archive of Our Own' and 'Tumblr' suggest anything, it's that I am certainly not the only person wondering.

|

| Source |

Just as a final note on Achilles/Patroclus before I move on, I mentioned above how immensely popular Miller's The Song of Achilles is. Part of the reason for this, I postulate, is Miller's use of beautiful, aesthetic language when portraying the inevitably tragic love story. You need only say 'This, and this, and this' or 'He is half of my soul, as the poets say' to a TSOA fan to make them curl up on the ground and weep.

But there is another reason, too. Some of you reading this may have experienced watching the Hollywood film Troy with me - if not, let me assure you, there is A LOT of shouting. In Art, Literature, and Culture from a Marxist Perspective, McKenna (2005) writes that 'The Song of Achilles provides a welcome tonic' to 'de-gayifying' adaptations of the Iliad, such as the 2004 film that stars Brad Pitt. McKenna (rightfully) accuses Troy of 'eviscerating the original storyline' in which Achilles kills Hector and dooms both himself and Troy, due to his grief at losing his lover. McKenna asserts that the romance between Achilles and Patroclus is immanent in the Homeric original, and thus 'Miller's work should be understood in the most radical way possible' because 'It is not simply that she interprets the best aspects of the Iliad through her novel: rather, she allows the Greek epic to become fully itself'.

Okay, I can tell I'm losing you, I'll move on.

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion

This is the last one, I promise.

|

| Source: 'Hephaestion' wikipedia "tight man-to-man friendship" |

Okay, there is so much evidence proving that Alexander and Hephaestion were lovers. Including the fact that their tutor, Aristotle, described them as 'one soul abiding in two bodies'! Clever bloke, that Aristotle. In their own letters, Hephaestion wrote that 'Alexander means more to us than anything' and Alexander wrote, after Hephaestion's death, that he was 'the friend I valued more as my own life'. Diogenes of Sinope famously wrote a letter to Alexander, in which he accused him of being 'ruled by Hephaestion's thighs'. Remember the stuff about intercrural sex in the last blog post?

The other reason why I wanted to bring up AtG and Hephaestion was that, just as their relationship was compared to Achilles and Patroclus', Madeline Miller's The Song of Achilles is compared to Mary Renault's Fire From Heaven. The novel is a fictionalised account of Alexander the Great's life, with particular focus on his relationship with Hephaestion: 'Hephaistion had known for many ages that if a god should offer him one gift in all his lifetime, he would choose [Alexander]. Joy hit him like a lightening-bolt' (Renault 1969). Unfortunately, the novel lies outside the scope of my thesis; although it is thematically relevant, the earliest novels that I work with were published in 2005 - 1969 is just too far of an outlier for me to justify! It is, however, still important to recognise the history of adapting the stories of queer men in antiquity by modern women.

Cover art: Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus, Sir James Grant 1760-3

Comments

Post a Comment