This weekend, I’m giving a talk at the Scottish Maritime Museum in Irvine, as part of their summer “Sea Monsters!” exhibition. For those of you who can’t make it, or for those of you who came to the talk but want to refresh your memory on it, here's a blog post!

We know more about outer space than we do about the leagues and leagues of ocean all around us. It is no wonder, really, that seafarers throughout the centuries and across cultures have returned home with fantastical stories. These include in their vast potentiality the promise of pleasures and riches, like a beautiful mermaid to love or, in Greek myth, the Fortunate Isle of the Hesperides, a winterless paradise populated by all the heroes; or, the Celts had the Tir na Nóg, the land of eternal youth.

Sailors also came home with tales of fantastical monsters that they glimpsed, or that tricked them or bewitched them, or that ate their crew.

Kelpies

|

| The Falkirk Kelpies statues |

Kelpies are shapeshifters, but their main form is that of a large black horse, with eternally wet manes. In this form, they aim to lure children into the water, where they can drown them. They typically shape-shift into alluring men, to seduce young beautiful women into the water… where they drown them. They also eviscerate their victims, for good measure, and many folk stories report that only the victims’ guts ever made it back to land.

Sometimes, they only transform partially, keeping the head of the horse, or, more typically, the hooves. Taking the form of a humanoid with hooves led to the association between the kelpie and the devil, which is alluded to in Robbie Burns’ 1786 poem ‘Address to the Devil’, where the devil is addressed by ‘whatever title suit thee,— / Auld Hornie, Satan, Nick, or Clootie!’ and whom Burns accuses of controlling kelpies: ‘water-kelpies haunt the foord / by your direction’.

In an 1887 edition of “the Celtic Magazine,” a monthly periodical devoted to the literature, history, folklore, and traditions for “the Celt at home and abroad”, the legend of the Kelpie is described as:

Like the power of fire, the power of water may be looked upon as malignant, as beneficent, or as merely kindly tricky. In Scotland, with its stormy seas and isles, and its short and rushing rivers, the water power is generally malignant. It appears, for the most part, as a horse, but it may, in its malignant form, be a young man of fair proportions, or it may appear as an old wife craving shelter and protection. (ed. MacBain 1887: 511)

The kelpies act as a cautionary tale for children and young women: don’t go near the water, or you will drown. This might be too abstract a concept, so let me tell you about the fluid beastie that haunts the nearby waters, waiting to drag you under.

We can further see this warning in the subtle distinctions between the kelpie and the water-horse. For some, they are interchangeable and, yes, they are basically the same creature, with the same malignant intentions. But some folklorists note a distinction: fresh water horse monsters are kelpies, while sea- and loch-dwelling beasts are water-horses (Kingshill & Westwood 2015: 350). So, whichever one you were geographically closer to, and therefore more likely to drown in, that’s the one you were likely to hear about.

Selkies

|

| Source |

The periodical says of Kelpies that ‘In its kindlier aspects, it may be the mermaid who is caught by the lucky swain while in deshabile in regard to her seal's skin. She lives with him happily for a period of time, but at an unlucky moment the seal's skin is restored to her, and she disappears.’

Deshabile means ‘partly-dressed’, so she is partly dressed in her seal’s skin. Here, the author has made the mistake of mixing up Kelpies and Selkies.

It’s Selkies who are mermaid-esque figures, beautiful women of the sea that wear seal skins.

A typical folk-tale is that of a man who steals a female selkie’s skin, finds her naked on the sea shore, and forces her to become his wife. He necessarily hides her seal skin to keep her imprisoned. But the wife will spend her time in captivity longing for the sea, her true home, and will often be seen gazing longingly at the ocean. This is the image typically rendered by artists. She might be forced to have children by her human husband, but once she discovers her skin, she will immediately return to the sea and abandon the children, even though she loved them. Sometimes, one of her children discovers or knows the whereabouts of the skin, so they return it to her, either unwittingly or to end her suffering. In some children's story versions, the selkie revisits her family on land once a year, but in the typical folktale she is never seen again by them.

In Barra, in the Western Isles of Scotland, there is a traditional folk song called ‘The Seal-Woman’s Sea Joy’, which was collected and recorded by musicologist Marjorie Kennedy Fraiser in 1910, that told the legend of a magical seal-maiden whose enchanted skin was stolen. Without it she couldn’t return to the sea, and so she agreed to marry the man who had taken it, but after several years living with him, when she was toiling over a hot stove and longing for the coolness of the waves, her little son came in carrying a strange thing he’d found that was softer than mist. It was her seal skin, and she slipped it on and dived into the ocean, leaving behind her husband and son. Though she did tell the son that if he and his father were ever starving, they could cast their net over a certain rock and she would fill it with fish (Kingshill & Westwood 2015: 323).

There's also a legend originating in Canna, called the seal-woman’s croon, that says all seals are really enchanted royalty, the sons and daughters of the king of Lochlann (the old Gaelic name for Scandinavia). Their wicked stepmother spent 7 years with a magician, learning the black arts so she could put a spell on the princes and princesses to make them half-fish, half-beast. Three times a year, when the full moon is brightest, they must return to their human shape, so they will feel the fullest sorrow at having lost their kingdom and their natural state, and anyone who sees them at such a time will lose their heart to them.

Once, long ago, a man of Canna was wondering by the seashore at night when he saw a seal-maiden in her human form and fell in love. Putting her to sleep with a charm, he took her in his arms and carried her home, but when she awoke, what should he find but a seal! Full of pity, he carried her back to the sea and let her swim away. (Kingshill & Westwood 2015: 327).

While the kelpies were symbols of the physical dangers of the water, the selkies symbolise the appeal of the ocean to men, to tame the untameable, to make the wilderness domestic.

The stories of selkies are stories of women taken without their consent, married and sexually assaulted, and forced into motherhood. Even the Canna legend, which varies from the traditional selkie lore in many ways, has a notable lack of consent: the stepmother transforms them without their consent, and makes them turn back periodically to remind them of the violation, and the man of the story effectively kidnaps and date rapes the seal-maiden, and he’s only unable to force her into marriage because she’s a seal in the morning.

Loch Ness Monster

Now, we couldn't have a proper discussion about Scottish sea monsters without including Nessie. The Loch Ness Monster makes its home in the largest freshwater loch in the Scottish highlands.

Reports of a monster inhabiting Loch Ness date back to ancient times. Notably, local stone carvings by the Pict depict a mysterious beast with flippers.

The first written account appears in a biography of St. Columba from 565 AD. According to that work, the monster bit a swimmer and was prepared to attack another man when Columba intervened, ordering the beast to “go back.” It obeyed, and over the centuries only occasional sightings were reported. As the Encyclopaedia Britannica notes, “many of these alleged encounters seemed inspired by Scottish folklore, which abounds with mythical water creatures” (EB, 2022).

But that’s only the beginning of Nessie’s impact. She –– for everyone seems to agree that she is a female mythical creature –– has continued to proliferate in the public imagination. In April 1933, a couple saw an enormous animal—which they compared to a “dragon or prehistoric monster”—and after it crossed their car’s path, it disappeared into the water. The incident was reported in a Scottish newspaper, and numerous sightings followed. In December 1933 the Daily Mail commissioned Marmaduke Wetherell, a big-game hunter, to locate the sea serpent. Along the lake’s shores, he found large footprints that he believed belonged to “a very powerful soft-footed animal about 20 feet [6 metres] long.” However, upon closer inspection, zoologists at the Natural History Museum determined that the tracks were identical and made with an umbrella stand or ashtray that had a hippopotamus leg as a base.

The news only seemed to spur efforts to prove the monster’s existence. In 1934 English physician Robert Kenneth Wilson photographed the alleged creature. The image—known as the “surgeon’s photograph”—appeared to show the monster’s small head and neck. The Daily Mail printed the photograph, sparking an international sensation. Many speculated that the creature was a plesiosaur.

The Loch Ness Monster continues to attract aspiring mythozoologists and monster hunters from around the world, and American TV channels like HISTORY and Paramount+ continue to create documentaries about Nessie. Despite the lack of conclusive evidence, the Loch Ness monster remains popular—and profitable. In the early 21st century it was thought that it contributed nearly $80 million annually to Scotland’s economy (EB, 2022).

The Kraken

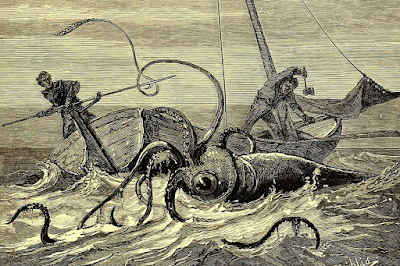

Originating in Scandinavian folklore, the Kraken is usually depicted as an aggressive cephalopod-esque creature capable of destroying entire ships and dragging sailors to their doom.

But did you know that a Kraken was once seen off the coast of Shetland? In the 19th Century, some men reported that it appeared like the hull of a large ship, but on approaching it nearer, they saw that it was infinitely larger, and resembled the back of a monster. Samuel Hibbert cited this in his text Descriptions of the Shetland Islands in 1822, and added that such beasts were thought to possess ‘tentacula as high as the mast of a ship’ –– in his research for the text, Hibbert heard several more accounts of Krakens and sea-serpents, ultimately concluding that ‘their occurrence is much connected with the demonology of the Shetland seas’ (Hibbert 1822 in Kingshill & Westwood 2015: 325).

Logically, what was identified as the Kraken was probably sightings of a Giant Squid, though Kingshill & Westwood also note the similarity between the Kraken accounts and the traditional descriptions of “Whale Island” –– so huge and covered with trees that sailors land on it and light a fire, provoking the creature to dive, plummeting them all to their deaths. The gigantic whale, named in medieval bestiaries as the Fastitocalon, was thought to have fragrant breath that lured fishes into its mouth; and a similar trait was reported of the Kraken by the Norwegian writer Pontoppidan (1857—1943) (Kingshill & Westwood 2015: 325-6).

The whale, and its cephalopodic cousin, the Kraken, both denote some very significant fears for the sailors of old. Fastitocalon the Whale is the fear of being beguiled, thinking that you have found land, found safety, a place to rest, only to find yourself dying at sea. The Kraken, in its mighty form, seems to me a reflection of the fear of the vastness and unknowability of the ocean, a fear we still have today.

In his 1830 poem ‘The Kraken’, Lord Alfred Tennyson warns us of the reemergence of these beasts:

Below the thunders of the upper deep,

Far, far beneath in the abysmal sea,

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth […]

There hath he lain for ages, and will lie

Battening upon huge sea worms in his sleep,

Until the latter fire shall heat the deep;

Then once by man and angels to be seen,

In roaring he shall rise and on the surface die.

***

Looking at a culture’s superstitions and folklores are really good ways of understanding what those people, at that time, were worried about. When it comes to islands, where the sea is at once depended upon and feared, both sea monsters and islands of magical promise proliferate. And, unlike some, in a sense, land-locked legends, sea monsters traverse from place to place, the same beasties cropping up in myths around the world, as sailors took to the seas and took their stories with them.

Bibliography

Comments

Post a Comment