In 2019, I asked you a question: How do you solve a problem like Helen?

I told you the broad strokes of Helen’s mythology, and then I told you why Helen is a bit confounding for modern feminist adaptations. Did she consent to go with Paris? Did she love him? Or, did she love Menelaus, and she was stolen by the Trojan prince? Or, did she not love either of them, and she made the choice because of a desire for … action, adventure, variety, notoriety &c.? Did she have any power to make the decision at all, or had she always just been the property of the men around her?

And here’s where the feminist perspective comes in because, honestly, none of these options are particularly empowering. Either she’s a master manipulator, in which women are vilified and blamed for men’s actions and she is a heartless succubus, or she's a powerless victim with no agency, blamed for a war which she played no active role in.

A more sympathetic view would be that none of these options make the war her fault. It’s Agamemnon’s fault for wanting to plunder the wealth of Troy; it’s not Helen’s fault, no matter whether she was abducted or chose to go, she hardly made the call to launch the thousand ships.

In ‘How Do You Solve a Problem Like Helen?’, I told you that she is rather difficult to adapt in modern feminist retellings, but she does get a fairly good showing in poetry and drama, such as in Carol Ann Duffy’s ‘Beautiful’, Margaret Atwood’s ‘Helen of Troy Does Countertop Dancing’, and Ellen McLaughlin’s rewrite of Euripides’ Helen.

I am yet to be able to answer the question ‘How Do You Solve a Problem Like Helen?’. In that blog post, I said: I think Helen’s mythology is in some ways too big to adapt. Did she love Paris? Did she choose to go to Troy? Did she want the war? What side did she want to win? Did she want to return to Menelaus, Sparta, and her daughter Hermione? Did she have any autonomy? These are some of the many questions that adapting authors would have to consider before adapting Helen. Perhaps poetry doesn’t require so much detail, and maybe drama works better with this inscrutability. Or, maybe, feminism still has some ways to go when it comes to dealing with beauty. Whatever the causes, it’s clear that Helen is a Problem™, but a fun one at that.

Attic red krater dated c.450-c.440. Menelaus [right] recovering Helen [centre]. The figure on the left is the goddess Aphrodite.

But now I’m going to tell you about some of the novels that do stage the “problem” of Helen, and solve it, in their own distinct ways.

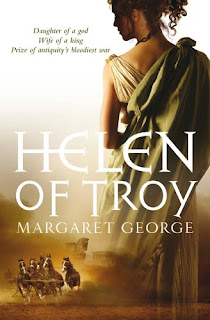

I am starting this ‘Solving the Problem of Helen’ series with Margaret George’s Helen of Troy (2006) for a couple of reasons. Firstly, because I do love a chronological order, and the scope of my thesis begins in 2005 (with Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad). Secondly, as a kind of reparation, because I put off reading the novel for so long. I really have no excuse, but I was intimidated by the fact that it’s nearly 800 pages long. I’ll tell you what, though, it was a mistake to put it off, because I absolutely bloody loved it. It completely took me by surprise: I loved George’s characterisation of Helen, I was really drawn in by Helen’s voice, and it was an absolute joy to hear

Every. Single. Event. Of. Her. Mythos. From. Her. Own. Perspective.

–– yes, it’s nearly 800 pages long, but it’s nearly 800 pages of Helen sharing her undiluted thoughts as she lives her life as one of the most famous women in history.

There is another reason why I am starting this series with George’s Helen of Troy. This is because it stands out among modern adaptations of Helen for portraying Helen’s relationship with Paris as a pure and beautiful love story.

As we shall see throughout this series, Helen’s relationship with Paris is rarely portrayed as a romance or, if it is, it’s a short lived one, as the scales fall from Helen’s eyes and she discovers what a vapid, preening man-child Paris is.

Apulian bell-krater, dated c.380-c.370. Helen and Paris; Paris is depicted with a spear, while Helen is seated with a fan.

But, no –– in George’s version, Helen and Paris are truly, completely in love. And isn’t that just lovely? To think that the decade (or two, according to some mythic traditions) that Helen spends with Paris isn’t as a prisoner of war, or as a bored and manipulated puppet, held up as a status symbol and ignored as a person, as a woman. No, in George’s version, it’s a beautiful and protracted honeymoon in the idyllic Troy, with the war as a dark backdrop to the central love story.

And if that sounds familiar, that’s because it’s a lot like what Madeline Miller does with Achilles and Patroclus in The Song of Achilles, where their beautiful love contrasts to the brutal war.

‘the face that launch'd a thousand ships, / And burnt the topless towers of Ilium— / Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss’ (Marlowe 1604: l.163-4)

This line is again paraphrased by Carol Ann Duffy in her poem ‘Mrs. Faust’, in which the modernised Faust remarks ‘The face that launched a thousand ships. / I kissed its lips.’ (Duffy 1999: l.93-4).

Indeed, In ‘Helen and the Faust Tradition’, Maguire states that ‘It is, it seems, impossible to write about Helen of Troy without invoking Marlowe’s lines’ but Marlowe’s lines are, crucially, not addressed to Helen herself, but to a demonic eidolon (Maguire 2009: 175).

Let that sink in for a second. The most famous quotation about Helen is not about Helen at all.

What does this mean?

It means that Helen is at once the most famous woman in history, the most beautiful, and the most shadowy, unknowable figure. She is, ironically, faceless.

Elizabeth Taylor as the silent Helen of Troy

in Richard Burton's Doctor Faustus (1967)

Why do I bring this up now?

Because Margaret George’s Helen is haunted by these words:

‘. . . And burnt the topless towers of Ilium. The words twined themselves around my mind. Topless towers of Ilium . . . someone else framed those words, and whispered them to me then, someone who lived so long afterward that he saw Troy only in his dreams, but he saw it clearer than anyone […] . . . or perhaps Troy was always only a dream.’ (George 2006: 283)

Much like Le Guin’s Lavinia being haunted by the future ghost of her poet, Virgil, George’s Helen is haunted by Marlowe’s famous lines about her, and her fate.

What we’re seeing here is another instance of a mythical woman contending with, and outright interrogating, her mythos and enduring reputation.

That's not to say that Helen meekly accepts her legend, though. Indeed, in a direct subversion of Marlowe’s lines, spoken by Dr. Faustus and echoed in Helen narratives ever since, George’s Helen narrates:

‘Paris. I kissed his lips,’ (Ibid., 229).

In this novel, we get a Helen who does the kissing, and not because she is a bored wife in Sparta, or because of some political manoeuvring, but because she enthusiastically consents to being with Paris.

‘People as yet unborn will make songs of us,’ (292) Helen prophesies, so –– as Margaret George’s novel asks –– why not make some of those songs with a happy, loved, and (finally) seen Helen?

Cover image: The Love of Helen and Paris, by Jacques-Louis David, 1788.

Comments

Post a Comment